Balancing the Harms and Benefits of Electronic Prisoner Communication

The following is an excerpt from Equal Future.

In South Carolina, inmates face up to two years in solitary confinement for making just one post to Facebook. It’s one stark frontier in an ongoing battle over the pros and cons of cell phone and internet access in prisons.

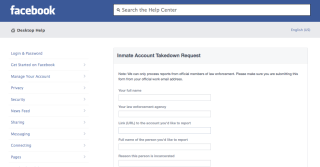

Many inmates are prohibited from using cell phones or the internet. However, the California Department of Corrections has confiscated more than 30,000 cell phones since 2012, according to an in depth investigation by Fusion (a new technology web site with a social impact focus). The investigation also “turned up dozens of social media profiles of inmates currently serving time in several states.” Prison officials are worried that inmates can use cell phones to “have unmonitored conversations that could further criminal activity, such as selling drugs or harassing other individuals.” They offer stories of inmates who have used cell phones to order killings of eyewitness and corrections officers. Internet access, whether on a smartphone or a computer, could be used to achieve the same ends.

Given these risks, some correctional facilities have gone to great lengths to prevent inmates from communicating with others through cell phones and/or the internet. Some correctional facilities in New York use chair-shaped magnetic scanners to detect metal objects, such as cell phones, inside body cavities. California, Georgia, Maryland, Mississippi, and Texas have used “managed access systems,” which intercept calls from nearby phones before they are sent to carriers’ towers. Furthermore, the South Carolina Department of Corrections (SCDC) has made it a separate Level 1 offense (the same level as homicide or sexual assault) for each day that an inmate posts on a social network site, writes Dave Maass of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). Under this policy, inmates can receive up to 720 days of solitary confinement per offense. One inmate was sentenced to 37.5 years in solitary confinement for making just 38 posts on Facebook. “In other words, if a South Carolina inmate caused a riot, took three hostages, murdered them, stole their clothes, and then escaped, he could still wind up with fewer Level 1 offenses than an inmate who updated Facebook every day for two weeks.”

Despite significant efforts to keep inmates from accessing cell phones and the internet, some argue that the ability for inmates to connect with the outside world isn’t really that harmful. Many inmates use cell phones for purposes that do not threaten anyone’s safety, like communicating with friends and family, posting videos of themselves dancing, or organizing hunger strikes. Some research, including a study from the Minnesota Department of Corrections, show that human interaction decreases recidivism: that study found that felons who were visited in prison were 13% less likely to be reconvicted than those who weren’t visited. “For every one [prisoner] who is a problem, nine more just really want to connect with society,” said Michael Santos (author, teacher, and former prisoner) to Fusion.

“Balancing the rights of inmates with public safety is a tricky task, but prisons… must consider proportionality and fairness for justice to be truly served,” writes Dave Maass of the EFF.